Contents:

Music

Reviews

Series selected as 'Books of the Year'

Twenty Books

Seventy Islands

A hundred and twenty maps & plans

Three thousand four hundred pages

These books about the fascinatingly diverse world of the Aegean Islands are written with a rare combination of scholarship and passion. They are the fruit of three decades of occasional exploration followed by seven years of dedicated study of the islands. And they document, in a detail not attempted before, the wide range of art, architecture, archaeology, history, natural phenomena, fauna and flora of this island world.

At over 3,400 pages they carry more than twice the amount of information that is available from any other source. That space also gives them the possibility to cover a wide variety of subjects, and to look at those topics with unhurried precision. The exquisite wall paintings of Bronze Age Santorini; the mountain flowers of Samos; the secret rites of the sanctuary of Samothrace; the sponge divers of Symi; the earliest beginnings of European sculpture in the delicate Cycladic figurines; the fantasy architecture of the 1920s & 30s on Rhodes and Leros... whatever the subject, they not only describe but explain the evolution and story behind what the visitor sees and wants to know.

They are the ultimate resource for the interested and curious traveller.

We hope that they belong to a new generation of guides which appeal to the thoughtful visitor – to those who are not seeking the shallow, fractured, sound-bite information of the busy picture guides, but who want to penetrate to the heart and spirit and hidden joy of the places they visit.

Drawing this detailed portrait of the Aegean world involved several years of walking, much joy – because of the inexplicably uplifting light and air of the Aegean seascapes – and a lot of patience with the winds and weather that are still as unpredictable as they were when Odysseus set off home from Troy.

Sometimes, too, it was not just a question of walking or climbing: reaching a couple of the sites in this book involved leaving note-books and paraphernalia behind on the shore and taking to the water in order to swim to them. Others were only accessible by boat: and there were yet other things about the islands that could only really be understood from the air.

However daunting it seemed, it was always an enjoyable challenge trying to get to see everything – every bit of ancient stone, the inside of even the humblest cliff-top chapel… and summit after panoramic summit of the island mountains. Everything needed to be looked at – because what could be the value in writing about something that hadn’t been seen?

The origins of the project

These books began with a commission to write a new Blue Guide which was to cover just the Greek Islands. This explains the initial approach and the lay-out of the books. Although they are more literary in character and go further and deeper than a traditional Blue Guide can go, they would not have come into being without that original commission or without the foresight and support of both the publisher and chief editor of the Blue Guides series.

It was not long before it became clear that there was going to be far more material here than could fit between the covers of one book, and so the idea evolved of producing first a cropped version of the manuscript, currently published as the Blue Guide to Greece: the Aegean Islands, and then going on to produce the full manuscript separately in several volumes. The solution worked well: and the product is this series of books – pocketable, practical, specific, and enjoyable companions for any journey to this magical corner of the world.

For better or for worse, these are not typical ‘guide-books’. They are literary, integrated portraits of the islands, drawn out in three dimensions: along a historical axis, a topographical axis, and a spiritual axis. By the last, I mean that they explore the human spiritual worlds which lay behind the places they describe: the rites practised in ancient Greece, the intentions of the painters and builders of the humble Byzantine churches, or the aspirations of the Island refugees who created so much of modern Greece.

With the sole exception of Crete, this series covers all the Greek, Aegean islands from tiny Antikythera up to Samothrace, and from the Lesser Sporades off the north of Alonnisos down to Kastellorizo, riding at anchor just off the southern coast of Turkey. One day it would be satisfying to complete the series by producing volumes on Crete and on the half-dozen important Ionian Islands off the west of Greece. But that all depends whether time and destiny permit.

The sound of the Aegean world... Extract from a Greek zeibekiko ('Το Μινοόρε του Τεκέ'), by Ioannis Chalkiás, 1932.

How the guides work

Each island – famous or little-known – has its own volume, or chapter of a volume. The study begins in each case with an introduction, setting the island in its context and elucidating particular aspects of its individuality:

Back to top

History

The introduction is followed by a history of the island from prehistoric to modern times, and a brief discussion of its early legends and myths:

from NAXOS

Legend

Zeus himself is associated with the island, not just in name – Mount Zas, and the former name of the island, ‘Dia’ – but by a tradition relating that it was on the island’s peak that an eagle gave him the gift of thunder. Above all it is his son, Dionysos, who is most closely connected with Naxos and remained the island’s presiding spirit throughout antiquity. In one version he was committed as an infant by Zeus to the care of nymphs on Mount Koronos, and grew up in a cave there. It was also on a journey to Naxos, that the Tyrrhenian pirates or sailors of his boat, not recognising the god, planned to kidnap him and sell him in the slave-markets of Asia. Dionysos turned their oars into serpents, immobilized the boat with riggings of vine leaves, and filled the air with the sound of invisible flutes – so greatly frightening the sailors, that they leapt overboard and drowned. The island is best known, however, from the story of Theseus’s leaving of Ariadne on Naxos (see box below) while on their way back from Crete to Athens. Dionysos found her abandoned and grieving, conceived a love for her, and had a number of children by her. The story is celebrated in one of the most accomplished poems of Catullus, in a masterpiece by Titian, and in an unusual opera by Richard Strauss.

History

Throughout the Bronze Age, Naxos played a leading role in Cycladic culture. This had been preceded by a strong Neolithic presence on the island, both in the heights of the interior – in the cave of Zas (c. 750m a.s.l.) – and by the shore. Although there were many Early Cycladic settlements scattered around the island, as is indicated by the great number of cemeteries, the only one to survive vigorously and continuously throughout the Bronze Age was the substantial settlement at Grotta on the north shore of today’s city of Naxos. This remained the island’s main trading centre throughout later Mycenaean times, and it preserved enough population and momentum to survive the difficult centuries after the destruction of the Mycenaean world. In the 8th century bc, Naxos planted a (homonymous) colony in Sicily, and one on Amorgos (Arkesine). The island was never divided into city-states but constituted a single state, with its city on the site of the present town.

Because of its wealth of natural resources the island entered the historic period in a position of advantage. “Naxos was the richest island in the Aegean” (Herodotus V, 29). Its deposits of fine sculptural marble and emery (see box below), together with the fertility of its interior, meant that it was able to dominate the Ionian group of islands and their sacred centre at Delos. The 6th century bc sees a remarkable flourishing of marble sculpting and building, in which Naxos, together with Samos, led the Greek world in innovative technique and designs in both areas; evidence can be seen of this in the grand monuments built by the Naxians both on the island itself, and at Delphi and on Delos. In 536 bc a civil war resulted in the overthrow of the landowning class and the instating of a tyrant, Lydgamis – himself an aristocrat, but a champion of the lower classes. In this period some of the island’s most signal monuments were raised. Lygdamis was overthrown in 524 bc, and after a brief oligarchy, democracy was established. In 506 bc the island successfully withstood a four-month siege by Aristagoras, Tyrant of Miletus, supported by a group of disaffected Naxiot oligarchs in exile. At the end of the century the island was at the peak of its power and influence: Herodotus suggests (V, 30) that Naxos could raise an army of 8,000 hoplites, in addition to the fleet it possessed.

Naxos’s ‘golden age’ ended with the Persian Wars. The island was devastated and its sanctuaries burnt by the Persians in 490 bc. It nonetheless fielded 4 ships to join the Greek fleet at Salamis in 480 bc, and fought at the Battle of Plataea. In 479 bc it joined the Delian League: but it was not long before it began to feel the oppressive hegemony of Athens and, recalling its own former power and glory, it attempted to secede in 473/2 bc. The Athenians firmly put down the revolt, subjugated the island, settled 1,000 clerurchs, and imposed a heavy annual tribute. Naxos never again regained its former status. In 377 bc, in the straits between Paros and Naxos, the Athenians routed the Spartan fleet with whom Naxos was then allied, and the island was forced once again to capitulate to Athens. In 338 bc the island came under Macedonian rule, then Ptolemaic rule, and finally under the Romans in 41 bc, who used it as a place of exile.

Saracen raids in the 7th century ad, forced the abandonment of the coastal settlements; but the island had a large enough interior which was agriculturally self-sufficient to remain unscathed. The surprising number of important churches of the 6th-9th centuries with decorations – some with strictly abstract designs dating from the period of the Iconoclastic debate – suggests that there was a quality of life on Naxos not known elsewhere in the Cyclades in the same period. Historical documentation is exiguous, however, for the period of Byzantine dominion. In 1207, in the aftermath of the 4th Crusade, the island was taken by the nephew of Doge Enrico Dandolo, Marco Sanudo (see box below) who established a Venetian ‘duchy of the archipelago’ based in Naxos. The extraordinary renaissance of church building and decorating on the island in the 13th century is ample testimony of the prosperity and security that this brought. His descendents, and the succeeding dynasty of the Crispi, ruled over Naxos and the Cyclades for 360 years... (continued)

Back to top

Topography

The island is then described through a series of logical and easily-followed topographical itineraries which cover all the monuments, collections, curiosities and points of interest. The descriptions were mostly sketched out on site, so they help the reader to see clearly how to explore a town, an excavated site, or a museum collection, and to distinguish the crucial items from the less important ones:

from KEA

The town of Ioulis or Ioulida (Chora)

Already in the parking area below the town, a large fragment of fluted column announces the antiquity of the site. Higher up, as you enter the habitation, on the right-hand side beside the Ethniki Trapeza is a doorway whose marble frame is composed of three re-used ancient, marble architectural elements: the lintel-block was re-carved with Byzantine motifs and an inscription in the early 19th century. The town today officially keeps the name of its pagan predecessor, Ioulis (or ‘Ioulida’ in the more demotic form), but is generally referred to as ‘Chora’.

The entry into the town is through a passage under buildings; such ‘stegadi’, as they are called, are a common feature of the urban architecture of Chora. The street to the left out of the tiny square beyond leads up to what was the acropolis of the ancient city, where the Temple of Apollo once stood. As you climb the steps beyond the church of Aghios Charalambos, you are confronted to the left by a stretch of Archaic fortification or retaining wall in large rectangular blocks, on top of which rises the smaller, irregular masonry of the Venetian kastro built by Pietro Giustiniani or Domenico Michieli around 1210, most of which was taken down in 1865. All that now remains is the long, arched gate-house, with its series of placements for gates. The interior of the kastro is occupied by municipal school buildings and other modern structures, but it offers a good view of the superb amphitheatre of whitewashed houses densely packed on the slope opposite. The individual units are simple – similar to the architecture of Dryopis on Kythnos – but, seen as a whole, the expanse is impressive. Little by little pitched roofs have come to substitute the original flat roofs over the last 150 years: this explains why, when the Bents lodged here in 1883, they observed that the inhabitants circulated in the town from roof to roof, tending to avoid descending into the streets which Bent complains were dirty and full of pigs.

The Archaeological Museum

A short distance up the main street to the right of the entrance into Chora, in a custom-built structure is the *Archaeological Museum, a fascinating and beautifully displayed collection of great quality – alone worth the visit to Kea. (Open daily, except Mondays, 8.30 am to 3 pm. €2) There are two floors: the First Floor exhibits the Archaic, Classical and Hellenistic collection; the Second Floor displays the remarkable prehistoric material principally from Aghia Irini. For chronological coherence, we begin with the latter.

Second floor (2 rooms). The earliest items are in the first three cases of Room 1 – Neolithic objects from Kefala; followed by Early Bronze Age items from Aghia Irini down the right-hand side of the room. Worthy of particular note are: the Late Neolithic bowl (#6), which bears the impression of a fine toothed spatula used for finishing the inside of the bowl, as if it were a marble object; and the delight in a subtle variety of different materials among the Early Cycladic stone mortars and pestles (#35-46), and of different forms in the marble figurines (#69-75). There is an elegant simplicity of design which carries through from the Late Neolithic marble conical cup ( #12), to the Early Cycladic objects, such as the elegant ‘depas cups’ (#82), similar to those found at Poliochni on Lemnos, and the ‘pedestal jar’ (#83) from Poiéëssa.

Room 2 contains the Middle Bronze Age finds from Aghia Irini including (centre display) the unique *statues of female figures with broad skirts, narrow waists, bare breasts and arms slightly raised – as if participating in some ritual dance, to celebrate or induce an epiphany. They astonish by both their size and their powerful form. What exact function they had, or what they represented, still eludes us however. It should be recalled that they were brightly coloured – the flesh painted white, and the skirts and the garlands around the neck tinted in fresh iron-oxide colours; they must also have been seen in relative darkness in the interior of the building where they were found. They were probably moulded on a wooden armature, in a clay which appears dense and gritty, even allowing for the rougher surface caused by erosion. Some appear to have a moulded band of plaited hair down the back. Few of the heads have survived intact, but those that have possess a very interesting design – mid-way between the schematic design of the head of the Cycladic figurine and the more developed physiognomies of the Daedalic statues of the early historic period (which in turn approach the Archaic faces that lie behind all later Greek sculpture).

Along the wall at the opposite end of the room from the window, are cases containing Late Cycladic pottery of the 17th to 15th centuries bc, whose magnificent *slip-painted designs are vigorous, confident and fresh – whether of marine creatures (#206), lilies (#213), double-headed axes (#191,193) or abstract designs (#200). Both the forms of the vases and their decorations possess remarkable energy.

First Floor. The principal interest on this floor is in the far room, where the exhibits convey a sense of the beauty and importance of the early 5th century bc Temple of Athena at Karthaia, through its programme of decorative sculpture. The many drill-holes and perforations in the marble indicate where the figures were embellished with affixed, additions in gilded bronze – for example the Gorgon’s head ‘aegis’ that would have been fixed on Athena’s breast (#65), or the helmeted head of Theseus (#20). The carving of the drapery and foot in the fragment (#86) of the north, pedimental acroterion is of exemplary gracefulness. All these pieces come from tableaux of sculpture (originally painted), which adorned the roof and gables of the temple, telling the story of the struggle between Greeks and Amazons, which culminated in Theseus’s abduction of Hippolyta (also called Antiope), Queen of the Amazons and daughter of Ares. The other items on display are also of high quality: the coins of Karthaia, with the head of Aristaeus on the obverse, and Sirius shining on the reverse, which compare interestingly in quality of image with the Athenian silver drachmae also exhibited; the selection of architectural elements, some with vestiges of colour and pattern still visible (#207); and a rare example of an inscribed plinth for a votive statue, with the fine bronze foot of the statue still attached and its lead dowelling visible.

Beyond the museum the main street climbs into the upper part of Chora. Below the buildings to the left (north) of the street are stretches of the enceinte of 6th century bc, defensive walls of the town: these are best seen from the lower terrace of the café, En Levko (‘ΕΝ ΛΕΥΚΩ’), just before the Town Hall. The Town Hall itself is a piece of very fine architecture dating from 1902 – neoclassical in design, with much of its decoration in good condition, including the two figures of Apollo and Ares standing on the attic balustrade. The *façade is particularly pleasing, with the unusual addition of a circular window-light for the central stairwell, just below the frieze. In the south wall of the building, a fragment of classical sculpture and of a low relief of figures at a sacred event have been immured in a small niche: in the interior of the building just inside the front-door, are a 1st century bc stele (left), and a mediaeval lion, emblem of Venice (right), to either side of the stairs.

Beyond the square of the Town Hall, houses climb the steep concave slope of the hill like seats in a theatre. The network of streets between them often passes under a ‘stegadi’ – one of the covered passage-ways that is a common feature of the island’s architecture –created by two connecting parts of the same dwelling which extend over the street.

The Lion of Ioulis

A 15-minute walk from the upper, east end of the village along an ancient, paved kalderimi which circles the valley to the north – passing several springs, the cemetery with its dovecote, and a number of scattered antique remnants – leads to the site of the *Archaic ‘Lion of Ioulis’, one of the largest and earliest pieces of monumental sculpture from the historic period in Greece. It is a remarkable and slightly inexplicable antiquity, which possesses little archaeological context and few points of comparison elsewhere. It is a boldly conceived image of a recumbent lion, about 6.4 m long, carved from the living rock. Its style suggests a date between c. 620 and 580 bc.

Purpose and meaning. The shape of the natural outcrop of rock may originally have given rise to the image and its pose; but it is hard to ascertain its purpose given the lack of significant context. Theodore Bent implies that it must have been at one end of an ancient stadium, whose rows of seats he observed in the vicinity when he visited in 1883. But it is difficult to see what a recumbent lion has to do with a stadium (which was presumably built later), and we have no other examples of such a combination. The sculpture’s isolation, however, would support the possibility that it may have marked an important grave. In later antiquity, sculptures of lions often marked burials: for example, the celebrated lion guarding over the grave of Leonidas at Thermopylae (now lost); or the still extant Hellenistic lion (of only slightly smaller size) at Krionerá, near Lavrion. Kea’s would then be one of the earliest, existing examples in Greece of lions as funerary monuments. The piece appears to be cut substantially free of the rock-bed, and the sculpted part sits on a well-finished shelf of stone which is a part of the whole. Underneath it has been provisionally shored up with blocks to prevent its slipping. This cavity could originally have been a place of burial.

There is another alternative: the area is rich in springs and it is not impossible that the Lion marked another, now dry spring which rose nearby, or even from under it. The reason for this choice of imagery would lie in the early mythology of the island, already cited above, which related how the native, spring-dwelling nymphs of Kea were frightened away from the island by a lion which descended from the mountains, and that their departure ushered in a period of prolonged drought. This climatic change clearly remained in the collective memory. When it was redressed much later by the intervention of Aristaeus, who created the altar to Zeus Ikmaios, the ‘rain bringer’, on the highest point of the island, and through his solicitations of the Olympian god caused cooling breezes, vegetation and water to return to the island once again, the lion that caused the problem in the first place was seen as pacified. A recumbent, resting lion was perhaps the best symbol of the animal’s pacification and would have been an appropriate tutelary image for an important spring.

Style. The stylised modelling of the tail, the ridge of the back, the haunches and the overall sinuous curve are typical of early Archaic work. The execution is beautiful, and never crude. It is probable that the Lion was brilliantly coloured at first. The head, and particularly the eyes, link it in time and style closely with the famous lions of Delos. The Delos lions have a clear, sacred, symbolic context, relating primarily to Artemis, and through her to Apollo: but no evidence of any Artemision has yet come to light in this area, and the temple of Apollo was on the acropolis hill of ancient Ioulis.

Over and above its stunning presence as a sculpture, the freedom of the piece lying unenclosed in the middle of the landscape, and the freedom of the visitor to examine it unhindered, make this one of the most moving antiquities in the Islands.

Back to top

Cartography

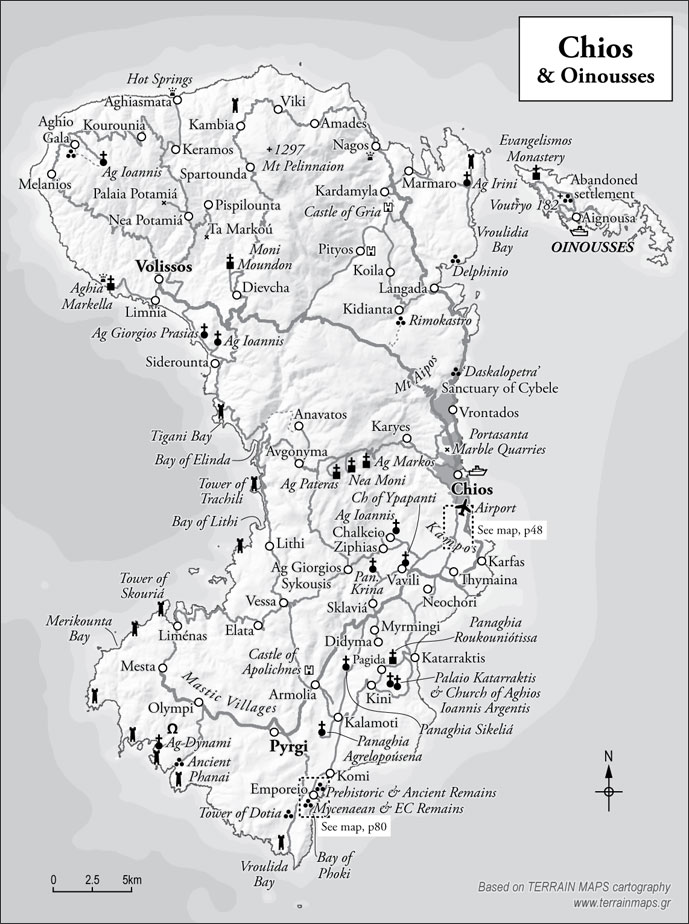

Each island has its own map showing road and path networks, with the places of interest mentioned in the text clearly marked:

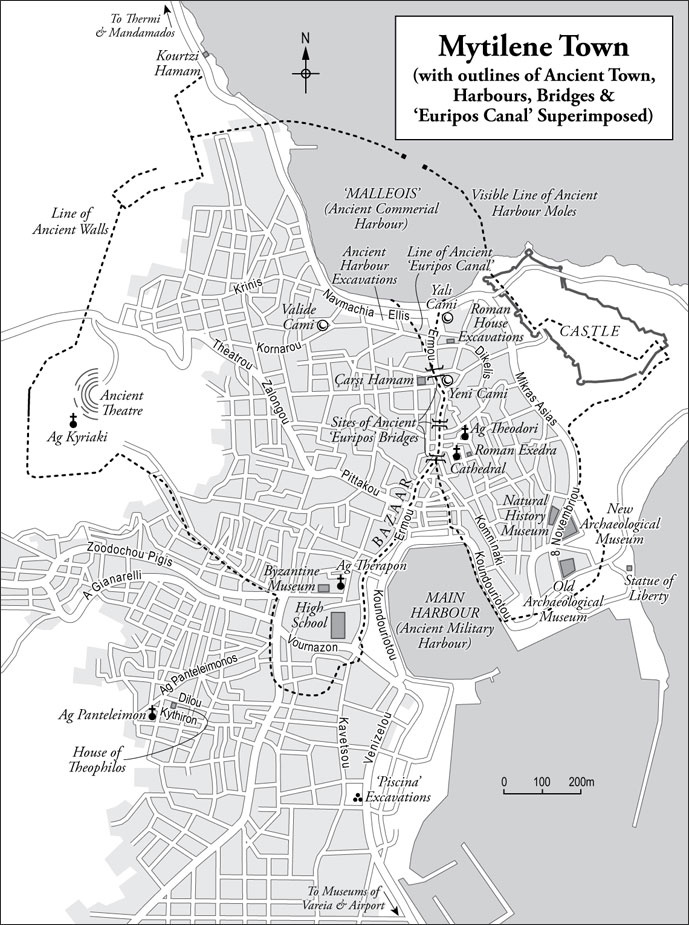

Larger towns and cities have dedicated street plans:

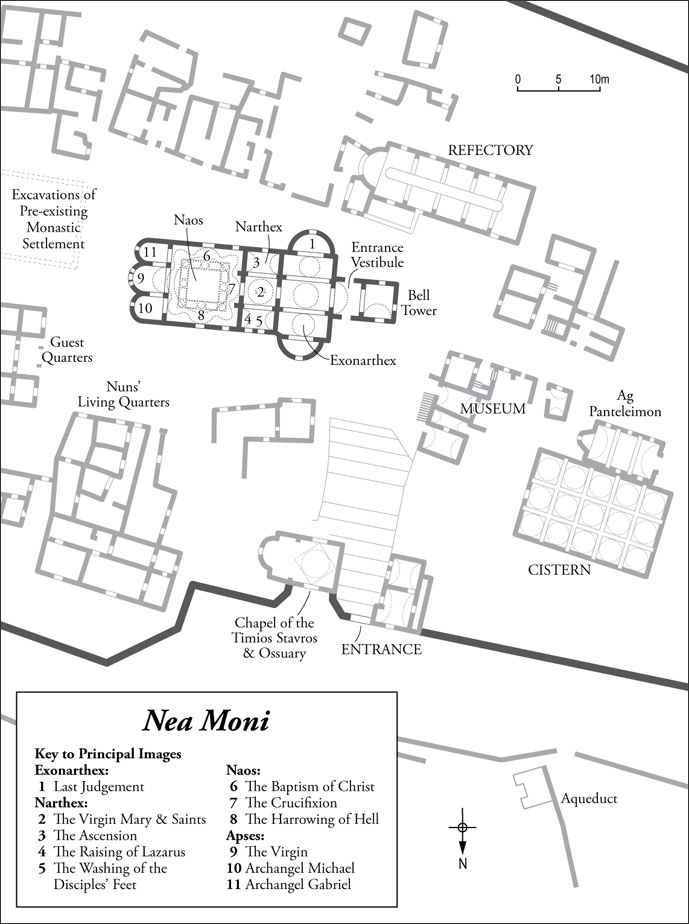

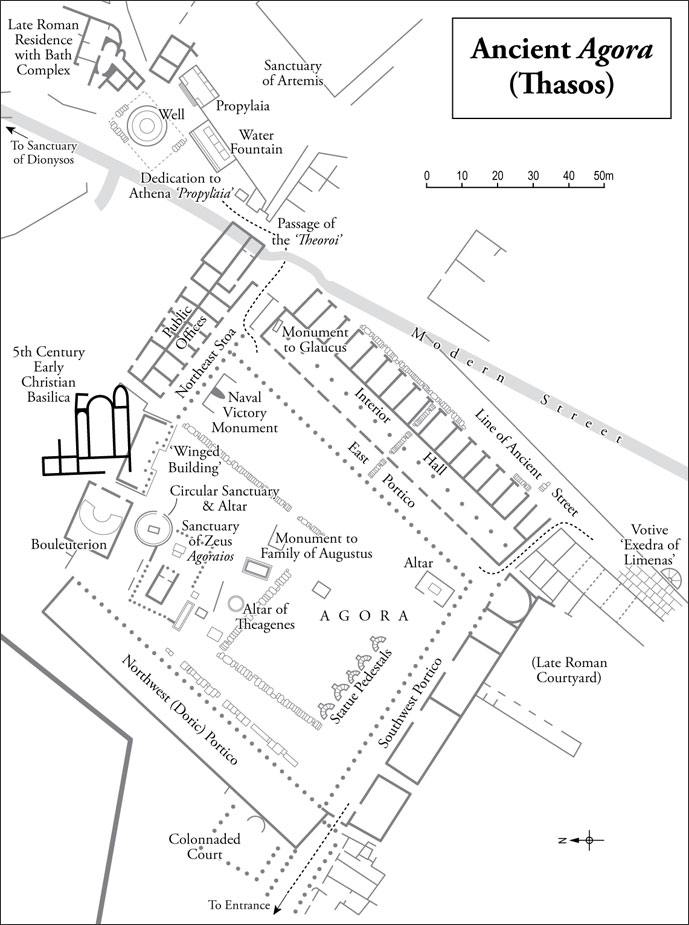

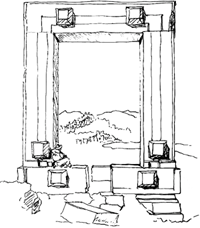

Important churches and archaeological sites have site- or floor-plans, to help the reader to orientate:

Back to top

Practical information

Finally, there is a brief section with practical information about the island and the means of access to it, as well as some suggestions of where to stay and eat. These books are not primarily ‘food and lodging’ guides, they are cultural guides: but we have indicated a small selection of places that we think might appeal to the readers of books such as these, and where good, local food can generally be had:

from LEROS

Practical information

85 400 Leros: area 54 sq.km; perimeter 82 km; resident population 8087; max. altitude 320 m. Port Authorities: 22470 22224 (Lakkí) & 23256 (Aghia Marina). Travel and information: (Lakki) Aegean Travel, 22470 26000, www.aegeantravel.gr: (Aghia Marina) Kastis Travel, 22470 22140, www.kastis.eu

Access: Leros has a small airport at the north end of the island (12 km from Lakkí), to which Olympic Air operates a daily (morning) summer service. There is also a flight three times weekly to Astypalaia, Kos and Rhodes. Two main ports are used on the island: the daily services by catamaran (Dodecanese Express), and four times weekly by car ferry (F/B Nisos Kalymnos) that ply the route between (Rhodes, Kos) Kalymnos and Patmos (Samos) call at Lakki; from the same port there are late-night ferries to and from Piraeus, four times weekly. The faster Flying Dolphins on the routes linking the Dodecanese Islands, use the port of Aghia Marina on the east coast of the island: these run daily in summer only. There are also local services to Lipsi and Patmos from Aghia Marina, and from Xerókambos to Myrtiés on Kalymnos. The latter is worth taking simply for the beauty of the scenery along the way.

Lodging. One of the dozen nicest places to stay in all the Greek Islands is on Leros, and is to be recommended above all else: the *Hotel Archontiko Angelou (tel. 22470 22749 or mobile 6944 908182; www.hotel-angelou-leros.com) in Alinda, is a fine 19th century, neoclassical mansion set in its own gardens a little way back from the shore. The rooms are comfortable and beautifully appointed without being over-decorated, the breakfast is excellent, and the setting in every way a delight. Price is moderate: a rental car is advisable. At the southern end of the island, in Xerókambos, the studio-rooms at Villa Maria (tel. 22470 27827) are very simple indeed, but are given life by the burgeoning flowers all around: the lodgings are peaceful, inexpensive and pleasant.

Eating. Some of Leros’s best eating places are mezé tavernas, serving a wide variety of small dishes to be taken together with an ouzo or wine. The Mezedepoleion ‘Dimitris’ has the most imaginative selection: it is signposted from a bend on the main Lakkí-Aghia Marina road above the north end of Vromólithos bay, and is hidden away beside the steps that lead down from the road. It has a terrace with a pleasant view. To Koulouki, beside the shore at Koulouki Bay just to the southwest of Lakkí, similarly serves hot and cold mezé on a peaceful terrace. For a shore-side setting of great beauty and for good quality fish, To Kima, on the eastern side of Xerókambos Bay is a reliable taverna. Locals, especially on Sundays, like to eat in the bay of Pandéli (south of the castle). There are three fish restaurants here; of these, Patímenos, is the most original and thoughtful in the presentation of its dishes, as well as the least expensive. But the liveliest experience and best value is represented by the small café, which produces a remarkable variety of mezés – situated in the tiny ‘square’ just in from the shore at Pandéli, where the one-way system turns sharply back up to Platanos and Aghia Marina.

The volumes have helpful glossaries and a more than ample index which make the books easy for consultation.

Back to top

Explanatory Digressions

A particularly enjoyable feature of the books are the many inset panels within the text which discuss in depth a wide constellation of topics which are mentioned along the way. These can relate to ancient wine, or coloured marbles, or unusual buildings, or ecology, music, rare birds, great battles, ancient rites, famous or eccentric individuals, and even the comparative properties of the natural hot waters you might want to enjoy on the islands... In short, everything you need or want to know.

Here are just a few extracts from the panels to give you an idea of their variety, and to whet your appetite to read these encyclopaedic books.

From Ikaria (vol 3), on the ancient wine from Mount Pramnos:

Pramnian wine

It was into a concoction based on cheese, fresh honey and Pramnian wine, that Circe poured the potion which was to turn Odysseus’s men into swine (Od. X. 635). In fact, Homer mentions the wine more than once, always indicating that it was mixed with grated cheese or barley: Plato, Aristophanes, Hippocrates, Diogenes Laertius and Athenaeus, also describe or refer to it. But common to them all, is the suggestion that the wine was almost never drunk pure or for refreshment, but was most often used medicinally for its highly nutritive qualities. What can such a wine have been like? Athenaeus of Naucratis, the connoisseur of all matters of the palate, describes Pramnian wine thus (Deipnosophistai, I.15): “it is a kind of wine that is neither sweet nor dense, but with a sharp and astringent and powerful taste”. He goes on to relate how Aristophanes was wont to say that the effete Athenians never took any pleasure either in hard and steadfast poets, or in Pramnian wine, or indeed in anything difficult which might “contract the stomach or cause a frown”. The wine was apparently “black”, was endowed with the “power to assuage anger”, and matured when left to stand (Hesychius of Alexandria). Eustathius, in his commentaries on Homer, says it was “not for quenching thirst, but rather for alleviating satiety” – perhaps somewhat like a modern ‘digestif’. Hippocrates and Galen speak of its therapeutic qualities, both for external application as an unction (Hippocrates) and for internal consumption (Galen). Much later, the French Jesuit missionary, Jacques-Paul Babin, again described the wine as “hard”, but added that the island had “the best winter grapes I ever encountered, being round and red, and growing between the rocks in such dangerous places that they are gathered with considerable hazard.” (The same Fr. Babin was astonished to note that the islanders of Ikaria rowed their boats naked, explaining to him that clothes were an impediment to them and wore out too quickly when rowing... (continued)

From Makronisos (vol 19), on:

The world's largest nautical wreck

On 26th February 1914 the sister-ship of the Titanic was launched in Belfast. The Britannic was 48,158 tons to the Titanic’s 46,328 tons. In the light of the fate of her sister-ship in April 1912 a number of modifications had been made to the design to make her safer. She came into being in inauspicious times, and her first journey was to be not as a luxury liner but as a hospital ship, when she was requisitioned in April 1915 to assist with relieving the mounting casualties from the Gallipoli campaign. In the autumn of 1916 she ran several missions between the Eastern Mediterranean and Southampton. Her sixth journey was to take her back once again to the Naval Base at Moudros Bay on Lemnos. She was under full steam in the channel between Makronisos and Kea in fair weather on the morning of November 21st when an explosion occurred which breached a hole in the starboard forepart of the ship, fatally damaging one of the watertight bulkheads. Even by sealing the remaining water-tight doors (one of which malfunctioned) the ship was flooding at an alarming speed and, as it began to list, open port-holes at the lowest level aggravated the situation. Within 55 minutes of the explosion the ship had sunk beneath water... (continued)

From Santorini (vol 1), on a curious summer festival in honour of Apollo:

Gymnopaidiai

In a famous incident recounted by Herodotus (Hist. VII, 208-9), Spartan soldiers, on the eve of the Battle of Thermopylae, were observed by a Persian spy, “stripped for exercise and dressing and combing their hair”: both the spy and his master found the behaviour astonishing. It was later explained to Xerxes by Demaratus – himself a Spartan aristocrat – that “the Spartans pay careful attention to their hair when they are about to risk their lives.” We, too, share Xerxes’s bewilderment: we would not have expected soldiers to have been seen setting their hair before departing for the Battle of Britain – something that suggests that attitudes to warfare have changed out of all recognition between the ancient and modern worlds. The observation is yet more significant because – of all the soldiers of history – the Spartans have the reputation of being the most seriously martial of all.

In a way that recalls aspects of Japanese culture, warfare in the Spartan mind was a sacred art in which the cult and perfection of the male body – its symmetry, its endurance and its performance – were part of a divine calling. This ‘cult’ meant more than doing physical jerks and running assault courses: it meant ritualising martial actions and physical discipline, and exalting organised movement in a group, which led to a vital subordination of the individual will to the larger unit. It also meant more than seeing the body as a machine – an accusation often made in ignorance against Spartan culture; it meant exalting the strength and endurance of a well-trained body as a divine gift, as an emulation of the most beautiful of gods, Apollo. The Greeks never sacrificed an animal that was not perfect and properly prepared: the Spartans at Thermopylae were not blind to the probability of their imminent self-sacrifice, and accordingly they prepared themselves to be fit for such a divine calling, by attending carefully to their hair on the eve of the battle.

Thera was a Spartan colony, and at the main feast in honour of its presiding divinity, Apollo Karneios, in the month of August, it organised sacred spectacles which, like those in Sparta itself, lasted several days. These were known as the Gymnopaidíai, which as their name implies (γυμνός, ‘naked’ or ‘unarmed’; παίζω, ‘I play or disport’) were performed probably naked, by boys who were passing from childhood into adulthood. They performed what appear to have been dances and martial sequences combining both musical grace and martial skill with the impressive endurance demanded by performing, as Plato points out (Laws, I p. 633 b&c), under heat of the August sun... (continued)

From Naxos (vol 17), on the origins of sculpture and its materials:

Marble and Emery

A pure white marble, of extremely fine quality, and a hard rock known as ‘black sand’ or emery, have together constituted the economy and the influence of Naxos throughout most of its history. Their importance is hard to overestimate: the foundations of marble sculpting for Western art were laid in Naxos, because of the quality of its primary material; and up until the last century, the island was the only major source of emery in the Western world for more than three thousand years. The two materials first visibly come together in the world of the Early Cycladic sculptures of the 3rd millennium bc: the white, translucent marble was sympathetic to the elegantly simple forms of the figurines and cups, and the softness of their contours could only have been achieved by painstaking working and polishing with the emery and pumice. The materials suggested the style; and the figures enhanced the materials.

Naxos marble is a prince among marbles: it is worth picking some up, handling it, and examining it in the light. Its regular crystalline structure is so open that it is almost translucent. That is why the ancient builders were able to roof the Temple of Demeter at Sangrí with marble tiles, and still be sure that the interior would be suffused with a gentle light. It is acknowledged among sculptors that the world’s most suitable marbles for sculpture are those from Paros and Naxos. Michelangelo and Bernini would have used them, if they had been more readily available to them. The Carrara marble which they used instead (and which the Romans called marmor lunensis) is perhaps purer; but it is quite different in character. Its colour is colder and bluer, and it is of a more regular and compact structure, imparting a ‘sugary’ quality to the stone: it is harder and less responsive to the chisel than Naxos or Paros marble, and it lacks their warmth and translucence. Nor do its crystals glint in such a lively fashion. Naxos was able to lead the Greek world in marble sculpting in the 6th century bc, because it had the best primary material, and as a consequence it produced, both for itself and for Delos, the greatest marble statuary of the age. Its hegemony was not to last for long, however: in the next century, Paros and Athens, both with enviable qualities of marble of their own, challenged her supremacy.

Emery is marble’s alter ego: much harder and stronger, and dark grey to black in colour. It is composed principally of corundum (aluminum oxide), mixed with small proportions of iron ore and magnetite. It abrades any softer stone, such as marble, without leaving scores or traces of colour, and can polish surfaces to considerable softness, especially when combined with volcanic pumice... (continued)

From Chios (vol 14), on the unique product of the island:

Mastic

The evergreen mastic tree (Pistacia lentiscus) is low, dense and ‘sculpted’ in form, with dark leathery leaves and a rough, corrugated bark from which it spontaneously weeps a pale yellow, largely odourless, resin or hardened sap. This ‘weeping’ can be promoted by making incisions (called ‘hurts’) in the trunk and branches of the mature tree and by harvesting the resin from June through to September; ‘hurting’ too young a tree, however, inhibits its growth. The sap coagulates as it drips from the cuts and is collected, rinsed in barrels, and dried: a second cleaning is done by hand. At its prime, a tree will yield 4.5 kg of mastic gum in one season. Many varieties of mastic trees grow wild throughout the Mediterranean area; but it is only on Chios, that the local Pistacia lentiscus chia variety, has become ‘domesticated’ and responded to intensive cultivation.

Dioscorides – observant writer on plants and herbs of the 1st century ad – mentions the mastic gum as used for attaching false eyelashes to eyelids (Materia Medica, I. 91): it was also known in antiquity as a treatment for duodenal ulcer and heart-burn. Christopher Columbus believed it to be a cure for cholera. But the most enduring quality of the gum has been its power, when masticated, to neutralize and to scent the breath. This was widely appreciated in the harems of Arabia and Turkey; 18th century reports suggest that the Ottoman Sultan kept half of the annual harvest from Chios for the Seraglio in Top Kapı – a quantity equivalent to about 125 tons... (continued)

From Rhodes (vol 6), on a valuable hostage:

Cem, Son of the Conqueror

In the austere world of the Order of St. John the exotic figure of the Turkish prince, Cem, sounds a note of colourful relief. In 1481, the year after the first siege of Rhodes, Mehmet II, conqueror of Byzantium, died and his succession was bitterly contested between his two sons, Cem (whose name, a contraction of ‘Jemshid’, is pronounced ‘jem’ and generally written ‘Djem’ or ‘Zizim’ in the west) and his more introverted elder brother, who went on to rule as Beyazit II. Thwarted in his bid for power, Cem turned to the Knights of St. John and negotiated a potentially risky political asylum in their hands, at first promising perpetual peace between the Ottoman Empire and Christendom if the Knights helped him overthrow his brother. He had had contact with the Knights before when he was Governor of Konya and the Southwest Provinces under his father. Grand Master d’Aubusson welcomed the possibility since the prince’s presence on the island, if handled correctly, could guarantee some measure of peace with the Turks. The prince was transferred to a Hospitaller galley at sea and later received in the city with great ceremony in July of 1482. The Master escorted him personally to his specially prepared lodgings beside the Inn of France. Illustrations from the contemporaneous Caoursin Codex show the prince being entertained to dinner by the Grand Master. When emissaries from Istanbul arrived to sue for the prince’s return, Cem was moved to France for greater safety in September of the same year. d’Aubusson exploited the situation adeptly, securing a yearly allowance of 45,000 ducats to keep the prince under permanent guard eventually in the castle of Bourganeuf in the Auvergne. In addition, Beyazit sent the Order one of Constantinople’s most precious relics – the right arm of St. John the Baptist which had been kept in the capital since the 10th century. The prince’s lengthy journey from Nice to Bourganeuf was punctuated with amorous intrigues in the aristocratic houses that offered hospitality along the way – at Roussillon, Puy and at Sassenage, where his host’s daughter, Hélène, became the object of his affections. In 1484 the circular, fortified ‘Tower of Zizim’ was completed at Bourganeuf to house the prince and his retinue: each day he bathed, versified, and drank spiced wine in spite of Koranic proscriptions. His poems are beautifully rendered in English by Elias Gibb, in his collection Ottoman Poems, published in London in 1882... (continued)

From Euboea (vol 9), on one of the many, beautiful coloured marbles from the Aegean:

Marmor carystium: 'Cipollino' marble

Of all the decorative marbles that the Romans extracted from the length and breadth of their Empire – from Aquitaine to the Egyptian Desert, from African Numidia to the Propontis – none had such apparent popularity or was so widely employed throughout the Empire as marmor Carystium, which was available in such inexhaustible quantities in the foothills of Mount Ochi, and emerged from nature in a never-ending variety of subtly different patterns. Elegant and cool in its delicate marine colour, with long, green-blue veins on a translucent background, it was never dull and yet never overly demanded attention. It enhanced any other marble combined with it, and above all set off the white marble of sculpture with exemplary elegance. It was abundant, resilient, adaptable to construction, and not difficult to work. The Renaissance stone-workers called it Cipollino (‘onion-like’) not so much because it has the appearance of sliced onion, but because the veins of mica which colour the calcareous body of the stone, cause it to be easily cut along the seams in the fashion of an onion.

Its illustrious career in Rome began, according to Cornelius Nepos (cited by Pliny, Nat. Hist. XXXVI 48) when it was introduced by Mamurra of Formiae, Julius Ceasar’s chief engineer in Gaul. It was extensively used in the Roman and Imperial Fora (Basilica Aemilia, Temple of Vespasian, the House of the Vestal Virgins, the Palace of Domitian, Forum of Trajan, Basilica of Maxentius etc.), its translucence and colour being preserved and refreshed by annual applications of a solution of chalk and milk... (continued)

Back to top

Purchase the books

Presentation Boxed Set of all 20 Titles

ISBN 9781907859205

Rhodes with Symi & Chalki

352pp (3 island maps, 5 site plans, 24 colour photographs) ISBN 9781907859236

Rhodes, with Symi and Chalki (Volume 6) has always been our largest and most popular volume in the series. In response to this we have undertaken a complete revision of the text, in collaboration with the experts of the Archaeological Service of the Dodecanese. We have also given the book a new colour cover as well as twenty-four, fine, colour illustrations inside.

Still the same level of detail; still the same dimensions; but a little more lavish to the eye, and with all the latest finds, changes and developments on the island included. This is a handsome addition to the series - and may be the first of more new versions of the other islands.

Back to top

Santorini & Therasia with Anaphi

120pp (2 island maps, 2 site plans) ISBN 9781907859007

Santorini is the Mother of Volcanoes (the crater left by the eruption of Karakatoa in Indonesia in 1883 - the largest of modern times - is between one quarter and one third of the size of that at Santorini). At about two hours before sunset the vast bowl of cliffs and islands below the town begins to fill with a palpable light reflected on the water from the declining sun. The murals from the prehistoric site of Akrotiri dating to the 17th century BC are among the most complete and beautiful to have been found so far. The siting of Ancient Thera is one of the most audacious in the Aegean: on three sides the mountain drops over 300m straight to the sea.

A fifteen minute ferry ride to Therasia gives a glimpse of what Santorini was like a few decades back.

Anaphi is the most arid of the inhabited islands in the Aegean. It feels like a forgotten frontier, remote and dramatic, whose interest lies in its surprises: the sanctuary of Apollo Aigletes, believed to have been first instituted by Jason and the Argonauts, the tiny church of Panaghia Kalamiotissa silhouetted against the sky, the finely decorated Roman sarcophagus lying in a field.

Kos with Nisyros & Pserimos

152pp (2 island maps, 2 site plans) ISBN 9781907859014

Kos has a wide and spacious feel. It holds an astonishing variety of remains from all periods of its long and important history. The town's skyline is exotically punctuated by minarets left by the Ottoman occupation and giant palm-trees left by the Italians. The most famous medical centre of Later Antiquity, in memory of Hippocrates whose name is inseparable from the island, lies close to the town and the island also has a large number of Early Christian churches.

Nisyros is the most significant volcano in the Aegean after Santorini: its circular perimeter, deep central crater, rich dark earth and several hot springs leave no doubt as to its recent geological origins. The bubbling fumaroles, vapour seams and sulphurous efflorescences of the different craters are fascinating to expert and amateur alike.

Pserimos is naturally one of the most tranquil corners of the Dodecanese, with a beautiful coastline and an undisturbed landscape of rocks and herbs and goats.

Samos with Ikaria & Fourni

208pp (3 island maps, 2 site plans) ISBN 9781907859021

Hera - powerful and often difficult Queen of the Heavens - was born on Samos and that fact meant that from earliest times the island was a particularly important centre of cult, with visitors and suppliants coming to it from all points of the compass. In the 6th century BC, under the firm and ambitious grip of the autocrat Polycrates, the island dominated Aegean waters and boasted a capital city which was unsurpassed by any other Greek city for its size and sophistication. The remains of this golden age are one of the prime reasons for visiting the island and the collection of archaic sculpture in the museum has no equals outside Athens. Samos is rich in its greenness and variety of landscape and its flora are impressive, with many unique and endemic species to be seen in its mountain massifs and over 60 different types of wild orchid recorded.

Ikaria presents a forbidding wall of high mountains, bearing the force of the winds from both north and south, but the island, particularly the west, has a landscape that is equally rewarding for the naturalist, the rambler, the anthropologist and the photographer.

Fourni has a heavily indented coastline and waters that are remarkably rich in fish and the island is a pleasant and quiet retreat with a delightful chora.

Mykonos & Delos

128pp (1 island map, 2 site plans) ISBN 9781907859038

Mykonos is a legend – a dry granitic island transformed into the upmarket tourist destination of today. It has become a place for those who desire their Greek island to be an extension of the city – cosmopolitan, busy, materially well-provided, a place to show off new clothes. The barren landscape of the island is adorned with 800 or so chapels and churches that seem to spout from every rock.

Apollo and Artemis, twin siblings, were born under a palm-tree on Delos. This divine association had the effect of supercharging this tiny outcrop into the most sacred place in the ancient Aegean and consequently one of the most important archaeological areas in the Greek Islands today. The site is immense. On the slopes of Mount Kynthos are some of the best preserved houses from the ancient Greek world, decorated with fine mosaics and painting, while the museum contains finds of astonishing quality. Nowhere else in the Greek world have the remains of a whole city and a sanctuary of such wide-ranging importance been preserved undisturbed by modern building.

Paros & Antiparos

96pp (1 island map, 1 site plan) ISBN 9781907859045

Paros produces what is considered traditionally to be the best quality of marble for sculpture in the world and many of the greatest sculptures of Antiquity – the Venus de Milo, Praxiteles’ Hermes, the Winged Victory of Samothrace – are made from Parian marble. The Panaghia Katapoliani is the oldest and most historically important church in the Aegean Islands. Paros has three beautiful towns – Parikia, Naousa and Lefkes – and its eating and beaches are among the best in the Cyclades.

Antiparos has a 15th century Kastro and a famous and impressive cave. Beyond it the deserted island of Despotiko has the most interesting ancient site currently being revealed, which may prove to be one of the most significant recent finds in the Cyclades.

Rhodes with Symi & Chalki

336pp (3 island maps, 5 site plans) ISBN 9781907859052

Cosmopolitan, spacious, immensely varied, blessed with a fullness of vegetation and an unforgettable radiance of light, the island of Rhodes has always been a proudly self-sufficient world of its own. The Hospitaller Knights of St John arrived in Rhodes at the beginning of the 14th century and fortified the island as a chivalric kingdom in the sea. Of all the cities in Greece, Rhodes is the only one that comes close to Athens in the density and richness of its monuments and in the sheer variety to be seen – Hellenistic, Mediaeval, Ottoman, Traditional, Italian Colonial – it substantially outshines the capital. Ancient Kameiros is one of the most untouched ancient archaeological sites in the Islands and few sanctuaries in all of Greece have a more improbable or panoramic site than that of Zeus Atabyros on the summit of the island’s highest peak. Three of the most complete painted Byzantine interiors in the Aegean are to be seen at Lindos, Asklepieio and Tharri and there are many smaller churches that should not be missed. The island is home to many unusual trees, flowers, reptiles, birds and butterflies.

In the 18th and 19th centuries Symi prospered remarkably from sponge fishing and boat building and its town became one of the most beautiful ports in the Aegean. Today the island lives by tourism and day-trips from Rhodes can seem to engulf the town. In addition to exploration of the town, a visit might ideally also include the discovery of the mountainous interior of the island and a journey by boat around its deeply indented coast.

Chalki today is a peaceful retreat, offering uncrowded beaches, scenic walks, a dramatic landscape inland and an attractive seascape all around formed by its outlying islands.

Argo-Saronic: Salamis, Aegina, Angistri, Poros, Hydra & Spetses

336pp (3 island maps, 5 site plans) ISBN 9781907859052

Salamis, forever linked with the sea battle that changed the course of history, has large areas that are effectively a suburb of Athens. The island also has attractive corners and plenty of interest, including the Mycenaean citadel of Kanakia, reached through a forest of pines and now thought to be the place where Ajax grew up, and the cave where Euripides is said to have retreated.

Aegina’s archaeological remains – the well-preserved temple of Aphaia and the ancient site of Kolona – are among the most interesting and important in the Aegean. The deserted site of Palaiochora, the capital of the island during the Byzantine period, with its many scattered churches constitutes a treasure-house of Byzantine painting. The landscape of the island with its many groves of pistachio trees is often beautiful and the summit of Mount Oros provides the best all-round panorama anywhere of the Saronic Gulf and the mountainous coasts of Attica and of the Peloponnese.

Angistri has a fine mantle of pines and its beaches are attractive.

Poros has an elegant town and a tranquil interior, where the important Sanctuary of Poseidon has a beautiful setting but as yet has only been explored to a limited extent.

At the beginning of the 19th century Hydra was a more important town than Athens and prospered from its commercial shipping interests, which endowed the island with one of the most strikingly beautiful ports in the Aegean. The rest of the island (where there is a total ban on motorised traffic) is only accessible on foot; the mountainous interior is grand and panoramic with a number of monasteries.

Spetses today is a place of contradictions, with widely diverging qualities of tourism and of architecture. The older buildings are languishing while new luxury housing flourishes. And, while non-resident cars are banned, motor-scooters create noise and disturbance in their place. The island’s celebrated pine forests have been decimated by repeated fires in the last fifteen years.

Kythera with Antikythera & Elafonisos

112pp (2 island maps, 1 site plan) ISBN 9781907859090

No visitor can fail to be struck by Kythera’s charm or by the variety of its sights: churches, landscapes, ruins, houses, caves, ravines , villages. Kythera’s most remarkable heritage lies in its numerous Byzantine remains and paintings, hardly surpassed anywhere in the Aegean outside Naxos. In addition to its classical sites, Kythera also has many pretty villages, waterfalls, mills, streams, hidden grottoes and beautiful beaches.

Antikythera has an undisturbed archaeological site at Aigilia, tranquil walks through the interior and remarkable bird life.

Elafonisos is best known for Simos beach, one of the most beautiful in Greece.

Euboea

160pp (4 island maps, 4 site plans) ISBN 9781907859151

The grandeur and beauty of Euboea’s landscapes are matched only by their constantly unfolding variety. The island is like a microcosm of all Greece: the northern tip has the feel of the wooded and bucolic landscapes of Corfu; the mountainous gorges of the centre are like parts of Epirus and Roumeli; the valleys inland of Kymi have a gentleness and a wealth of painted churches which remind one of parts of the Peloponnese; the area around Dystos feels uncannily like Boeotia; and the south of the island, hemmed by windy beaches, is wild and rugged in the grandest Cycladic manner. The mountains of Dirfys, Ochi and Kandili need exploring in turn, so as to discover that each possesses a strong personality, quite distinct from one another.

Sporades: Skiathos, Skopelos, Alonnisos & Skyros

140pp (4 island maps, 1 site plan) ISBN 9781907859076

Skiathos is famous above all for its dense pine woods and its magnificent sandy beaches. While the island’s south coast has intense tourist development, the sparsely inhabited and densely wooded north has been affected hardly at all. There are abundant walks to be made in the peace and shade of the hills in the interior. The deserted Byzantine settlement of Kastro, on a pinnacle of rock overlooking the sea at the northernmost point of the island, is a magnificent and dramatic sight.

Skopelos has the greatest depth of all the Northern Sporades islands, with its self-sufficiency, richness of architecture and commercial vitality. The appealing wooded coastline has coves and beaches and there are deep forest valleys in the interior. The town has an attractive and varied domestic architecture and an unparalleled number of interesting churches. In the hills to the north, east and west of the Chora are over a dozen monasteries.

Alonnisos has a stronger scent of pine and wild oregano in its air than almost any other island. Its waters are limpid, its forests are intact and its coastline is indented with enchanting coves and beaches. The island is the centre for the Northern Sporades Marine Park, the largest marine conservation area in Europe, set up to protect the habitat of the monk seal and other marine life in the scattering of beautiful islands to the north and west.

The tenacity to tradition on Skyros affects all aspects of life - local song and music, the decorating of houses, the breeding of horses, the preparing of cheese, the nature of festivals. The north of the island is fertile and densely wooded, while the south is wild and rocky. The island’s beautiful Chora is rich in a wide range of history and at Palamari is one of most important and impressive Bronze Age sites in the Aegean. The island is home to an ancient and unique breed of wild pony and there are quarries of a flamboyantly coloured marble that was exported in large quantities to Imperial Rome, while the south of the island has the moving and solitary grave of the young poet Rupert Brooke.

Thasos

112pp (1 island map, 3 site plans) ISBN 9781907859168

It would be perfectly possible to come to Thasos to enjoy its beaches, mountain walks, country tavernas and beautiful villages, but it would be a pity to stop at that: few other Greek islands will allow you to come closer to the lived history of Antiquity, to get a clear feel for an ancient city in its entirety. There are as many as eight separate sanctuaries to divinities that have been uncovered so far, a commercial and a military port, a chain of lighthouses to guide ships to the harbours, two theatres and the exceptional circuit of walls, masterfully built and perforated by almost a dozen gates. Outside the city, the beauty of the island’s coast and the peacefulness of its villages and landscapes can challenge anything found on the mainland opposite.

Lemnos with Aghios Efstratios & Samothrace

160pp (3 island maps, 2 site plans) ISBN 9781907859175

Lemnos has one of the most unusual landscapes of the northern Aegean islands – not only its mountainous west but also the grassy rolling expanses of the east have a character not encountered elsewhere. The island acquired importance very early on and Poliochni on the island’s east coast is generally considered to be the oldest organised city in Europe. The capital Myrina is dominated by an impressive Venetian castle and the villages and towns have an attractive local style of architecture.

In 1968 the town of Aghios Efstratios was razed to the ground by a massive earthquake from which it has only partially recovered. The interior of the island is mostly uncultivated and little frequented.

Samothrace has a solitude and grandeur that are epic. Its rugged gorges and peaks, its trees, waters, winds and shores possess something of primeval simplicity. It is perhaps no surprise that an important and very ancient cult should have evolved on the slopes of Mount Saos. Few Greek sites raise so many unanswered questions as the Sanctuary of the Great Gods. The walker, climber, naturalist or poet could ask for little more from an Aegean island. Goats are everywhere.

Lesbos

144pp (1 island map, 2 site plans) ISBN 9781907859106

Lesbos has a predominantly rural character, uncommon for an Aegean island. The central valleys and slopes carpeted as far as the eye can see with olive trees, the unusually tranquil waters of its two sea-gulfs that flood the heart of the island like large lakes, the self-sufficiency of its stately villages and the relative beneficence of its mountain peaks all contribute to give the island a feel of domesticity, spaciousness and calm. From Antiquity, Lesbos has less to show than its neighbours: the beautiful Hellenistic mosaic floors, exhibited in the New Archaeological Museum, are for the visitor its most vivid relic. But from the Middle Ages on, its heritage is rich: Byzantine rural churches, important monasteries, many Ottoman buildings and, most conspicuous and widespread of all, the beauty and rich diversity of its villages. The hot waters of Lesbos are one of the island’s greatest and most unusual attractions.

Chios with Oinousses & Psara

184pp (2 island maps, 5 site plans) ISBN 9781907859182

Grand and solitary, rich in architecture and flora, Chios is more than any island in the Aegean a world to itself. The refined mosaics of the great 11th century church of Nea Moni are amongst the most important in Greece. Unique to the south of Chios are the house-fronts decorated in grey and white designs in sgraffito technique, which constitute such an attractive aspect of the Mastic Villages. (The harvesting of mastic gum has never been successfully replicated anywhere else in the Mediterranean). In the Kampos area to the south of the city are beautiful stone villas, farmsteads and orchards built by the Genoese settlers in the 18th century. Chios has an open, rugged and dramatic coast, with some of the wildest highlands of the Aegean in its interior.

Oinousses still feels like a forgotten frontier. Its peacefulness, the wide views into Turkey and to Chios and the dense and unusually varied vegetation of its garrigue are its greatest attractions.

Psara is an island where visitors are not often seen. It has two interesting historic sites: the Mycenaean settlement at Archontiki and the fine Monastery of the Dormition.

Northern Dodecanese: Kalymnos, Telendos, Leros, Patmos, Lipsi, Arki & Agathonisi

200pp (5 island maps, 4 site plans) ISBN 9781907859113

Kalymnos delights with its combination of easy normality and vivid geographical contrasts: a skeleton of rock-bare mountains breached by shallow plains of intense green fertility; waters reflecting mountain ridges and summits shot through with caves that are famous among pot-holers and rock-climbers; and, set in contrast to all this ruggedness, the island’s capital Pothia which has a busy metropolitan feel. Even more than Kos, there is an astonishing quantity of Early Christian remains on Kalymnos and their greatest treasures are often their fine mosaic floors.

Telendos is notable for the Basilica of Aghios Vasilios and the deserted settlement of Aghios Konstantinos with its dramatic setting.

Leros has peacefulness, beauty and a wide variety of interest for its modest size. It has a coastline of magnificent bays, a handsome chora dominated by a dramatic castle, a number of interesting museums, early rural churches and villages that burst with flowers and trees amidst a landscape of rocky hills. The island’s principal harbour at Lakki was built in ‘Rationalist’ style in the 1930s during the Italian occupation.

Both in the imagination and in reality, Patmos is so dominated by the great Monastery of St John that it is easy to forget that there is a lot more to this beautiful island – not least its beautiful and architecturally interesting chora which even without the Monastery would be worthy of attention. The island also possesses a remarkably varied shoreline – deeply indented and modulated, often backed by dramatic hillsides or marked by offshore islets and eroded rock-stacks.

The islands of Lipsi, Arki, Agathonisi and their countless peripheral islets form a wide seascape of consummate and ever-changing beauty. This was in Antiquity the Milesian Sea and these islands lived by protecting and facilitating the immense volume of commercial traffic that passed in and out of Miletus. The best way to understand these islands is by boat, in order to capture some sense of what this corner of the Aegean was like in Antiquity.

Southern Dodecanese: Astypalaia, Tilos, Karpathos, Kasos & Kastellorizo

216pp (5 island maps, 2 site plans) ISBN 9781907859199

Perhaps no other island in the Aegean feels as dramatically spacious for its size as remote Astypalaia; the greater part of the island is populated most visibly by a remarkable quantity and variety of birds. Astypalaia has two artistic treasures of importance. Its splendidly sited Chora is one of the most beautiful in the Aegean islands. Second, perhaps more than any island other than Kos, it has a remarkable wealth of Early Christian mosaic floors dating from the 5th century.

In the last decade Tilos has distinguished itself from all other Greek islands by concertedly espousing the causes of wild-life and environmental conservation. The island’s dramatically varied landscape, rich in water and oscillating from steep mountains to fertile plains by the shore, helps to sustain its diversity of flora and wild-life as well as to provide countless walking opportunities.

Karpathos has the wildest landscape and coastal waters in the Dodecanese. Its northern half is a steep sculpted ridge of mountains that drop abruptly to the sea, while the southern tip of the island is an open landscape of soft eroded sandstone. The monuments of its past which remain today are characterised by a quality of unusualness: the site of Ancient Brykous projecting into the island’s northwestern waters is one of the Aegean’s most lonely; further south at Lefkos is a unique and well-preserved hypogeum of the Late Hellenistic period; another of the island’s ancient cities Arkaseia flourished into Early Christian times with at least two sizeable basilicas with mosaic floors of extraordinary quality.

Kasos today is a friendly and unpretentious island, small and easily walkable for the visitor.

Equidistant between Alexandria and Athens, Kastellorizo has admirably refused to be forgotten by history. Its ancient wine-pressing installations, fine burial places, impressive early walls and its network of cisterns are all evidence of an earlier thriving community.

Naxos & the Lesser Cyclades

192pp (2 island maps, 2 site plans) ISBN 9781907859083

Largest of all the Cyclades and with the highest peaks in the group, Naxos is the central geographical hub around which they all cluster. It has a patrimony of history, archaeology and monuments which puts it among the three or four artistically richest islands in the Aegean. It offers the grandest and most varied landscapes in the Cyclades; it is rich in water and its tranquil spring-fed orchards and olive-groves in the heart of the island considerably modify our customary picture of the dry ‘Cycladic landscape’. The striking beauty of the island is further enhanced by the numerous Byzantine stone churches dotted among the trees dating from the 6th to the 16th century and mostly decorated with paintings of great quality. The extraordinary unfinished kouros statues of the 6th century BC are a treasure-house of information about early sculptural techniques.

The waters of the Lesser Cyclades are among the most protected in the Aegean, shielded from the north winds by the great bulk of Naxos, and they can have the appearance of a lake in the middle of a ring of mountains and hills. Almost one third of the Early Cycladic figurines known today comes from the uninhabited island of Keros. Donousa and Herakleia are havens of tranquillity, while Schinousa and Koufonisi are developing fast into centres for visitors.

Northern Cyclades: Andros, Tinos & Syros

168pp (3 island maps, 3 site plans) ISBN 9781907859120

Andros strikes the visitor immediately as a quiet, reserved, clean and prosperous corner of Greece, well-treed and with water everywhere. Few other islands can offer such a wealth of shady walks, along valleys of running streams, amongst the flora, bird- and butterfly-life which they support,. This is above all a place for the rambler, the cultural tourist and those interested in visiting an island for its peacefulness, normality and unspoiled landscape. No visit should miss the well-preserved ancient tower at Aghios Petros; the small and beautifully clear archaeological museums at Palaiopolis and in Andros Chora; the picturesque villages of the interior, such as Stenies and Menites; the monastery of Panachrantos, the panoramic site of the castle at Apano Kastro and a tasting of the waters of the Sariza spring.

There is restless energy in Tinos and the sense of a ferment of activity – not just in the flow of pilgrims who come to pay their respects to one of Greece’s holiest icons, but in the terraces on the hillsides, in the beautiful dovecotes which dot every corner of the island’s landscape, in the lovingly carved details on the houses in the ‘marble village’ of Pyrgos and in the calmly bustling activity of the island’s intimate rural villages.

Syros has a feel quite different from the other Cycladic islands. The spacious, marble-surfaced elegance of the Neoclassical port Ermoupolis, the only true city in the Cyclades, is a vivid contrast to the usual labyrinthine streets of a Cycladic chora. The west coast of the island to the north of Kini is wild and uncompromising and seems a world away from the port.

Western Cyclades: Kea, Kythnos, Seriphos, Siphnos, Milos & Kimolos

272pp (7 island maps, 7 site plans) ISBN 9781907859137

Kea is unexpectedly rich in history and variety of landscape. The island is particularly good for walking; its valleys favour many species of wild flowers and its upland slopes support magnificent Valonia oaks. In historic antiquity there were four important cities on Kea and the remains of Karthaia constitute one of the most evocative sites in the Aegean. Most remarkable is the Lion of Ioulis, one of the earliest and largest pieces of monumental sculpture in the Greek world.

Kythnos has a peaceful rhythm of life which has changed little over time. There are two attractive villages Chora and Dryopida and plentiful hot water springs at Loutra in the northeast. The island’s repeatedly indented coastline affords a wide variety of small coves and beaches.

Seriphos has beautiful bays for swimming and offers many opportunities for walking, with a number of ancient rural churches along the way. What stays in the memory longest however is the image of the island’s dramatic chora, clustered around its peak far above the island’s harbour.

Siphnos is a delight to the eye above all and furnishes more abiding images than many of its neighbours: the stately villages of elegant 17th century churches and well-maintained neoclassical mansions; the rural valleys, full of dovecotes and chapels, watched over by both ancient towers and more recent monasteries from every summit; the chapels built improbably on rocks projecting into the sea; the ancient columns and sarcophagi that adorn the alleyways of Kastro. Aghios Andreas in the centre of the island constitutes one of the most interesting archaeological sites in the Western Cyclades.

The volcanic terrain of Milos gives rise to fascinating mineralogy: from the pure obsidian, which has been exported from Milos for at least 8000 years, to kaolin, haematite, alunite, manganese, bentonite, perlite, baryte and anderite. Milos is a busy working island with its population nearly all concentrated in the north; the south and west are wild and largely empty.

Kimolos is a delightful island: peaceful, unpretentious and full of striking landscapes. The northeast of the island is scarred by the quarrying of fuller’s earth. The Kastro of Chorio dates from the 15th century.

Southern Cyclades: Amorgos, Ios, Sikinos & Folegandros

136pp (4 island maps, 4 site plans) ISBN 9781907859144

The landscape of Amorgos invites dramatic settings. Few other islands combine as succinctly so much history and landscape and important archaeology as Amorgos. Walking on the island is perhaps the greatest pleasure it affords. The three cities founded in historic times - tactfully distanced from one another so as to divide the island into three equal parts – all occupy exhilarating summits or promontories. Two thousand years later, monks fleeing Arab incursions into Palestine took refuge on the island and established their community in the most impossible site of all - the Panaghia Chozoviotissa Monastery, half-way up a 400m precipice above the sea, is one of the most unforgettable sites of the Aegean.

Ios has a picturesque Cycladic chora and a number of the finest beaches in the Aegean. The island’s solitary beauty and grandeur have been compromised in recent years by the construction of roads and a boom in tourism. Recent changes in the local administration suggest that there is a will to redress some of the damage done to the island’s traditional social structure.

Sikinos is a remarkably tranquil island with much of its mountainous landscape wild and scarcely accessible. One of the most interesting and best-preserved Roman monuments in the Cyclades is the Monastery of Episkopi, a grand mausoleum which has survived by being converted into a Christian church. The settlements of Ancient Sikinos and at Palaiokastro are both remarkable for the alarming perpendicularity of their sites.

Few islands can boast a more attractive and dramatically sited chora than Folegandros, with its compact mediaeval centre and a chain of beautiful shaded squares. The island is delightful, with several civilised places to stay, pleasant cafes and many attractive beaches. There are a number of interesting walks along the island’s network of stone-paved mule paths with majestic cliffs on all sides.

Back to top

Reviews of McGilchrist's Greek Islands series

“So evocative and informative, one hardly needs to go... Lovely...”

Bettany Hughes,

Sunday Herald - Books of the Year

"For lovers of the Aegean, it is as close to being the definitive guidebook to the region as you are ever going to get."

Daily Telegraph

Read full article "A literary Odyssey of island life"

“... delightful, well-observed, literary accompaniments to the Greek islands, by a British scholar.”

The Economist,

Books of the Year

“There has never been a Greek islands guide like this one.”

James Campbell,

Times Literary Supplement

The guides "have a vivid, enthusiastic brevity that is infectious..."

The Oldie

Read full article, "The British Odysseus"

“Anyone who likes to explore the environment, history, and culture of the planet will instantly recognise the value of these books... [the] passion is endearing, and the accessible style in which the series is written makes them addictive...”

Mark Merrony,

in Minerva

“Clear explanations, combining fine detail with acute observation, intelligent interpretation and well-judged speculation provide a model for how the best can be got out of a complex site... For the committed investigator, these are essential buys.”

Peter Jones,

The Journal of Classics Teaching

a “remarkable achievement – a complete, island by island, 3,000 page survey of all the historical monuments in the Aegean...”

Barnaby Rogerson,

Country Life

“a real strength of these books lies in their descriptions of the Medieval and post-Medieval islands…. McGilchrist is at his best describing the ambience... in Naxos where there are more than 130 Byzantine churches...”

Andrew Selkirk,

Current World Archaeology

“... can only be praised, and will set a standard that has to be permanently recognised and valued.”

Paul Hetherington,

author of The Greek Islands: Byzantine and Medieval Buildings

“Wonderful... superbly structured; immense learning elegantly, unobtrusively offered; and outstandingly well written”

Prof. Jon Stallworthy,

Wolfson College, Oxford

“A work of astonishing scope, quality and insight.”

Charles Arnold,

author of Mediterranean Islands