Contents:

Contents of the book

Audio book

Music

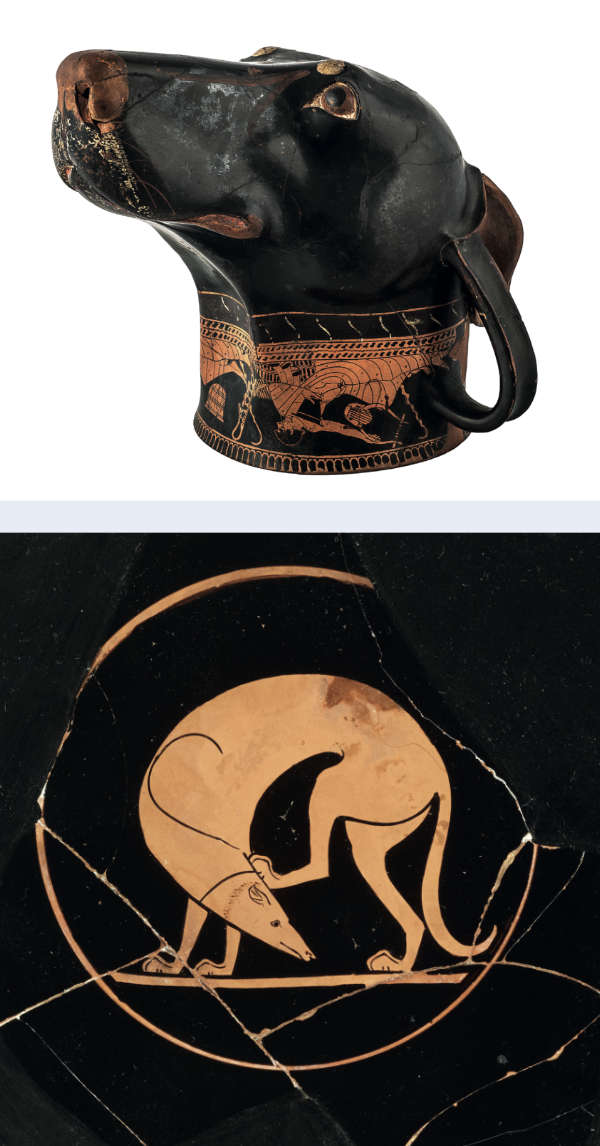

When the Dog speaks, the Philosopher listens

A guide to the greatness of Pythagoras and his curious Age

This is a book not of philosophy, but about how philosophy was born; about what it was like to explore the earliest, and most universal, scientific concepts. Exploration is fundamental to its theme, because the 7th and 6th centuries BC are one of the greatest periods of exploration in human history - explorations both mental and geographical; and many of them on a scale, and of a boldness, that impresses us profoundly today. It was also a period of extraordinary intellectual fertility and artistic development, right across the arc of Europe and Asia. In India, the Buddha began his teaching; in China, Confucius and Lao Tzu - or that group of sages, who sowed the seeds of Taoism; in Persia, too, (if we follow some chronologies) Zoroaster spoke; all this, at the same time as Greek philosophy and science were rapidly emerging, on the very edge of Europe, as a new and radical way to understand our universe and our existence within it.

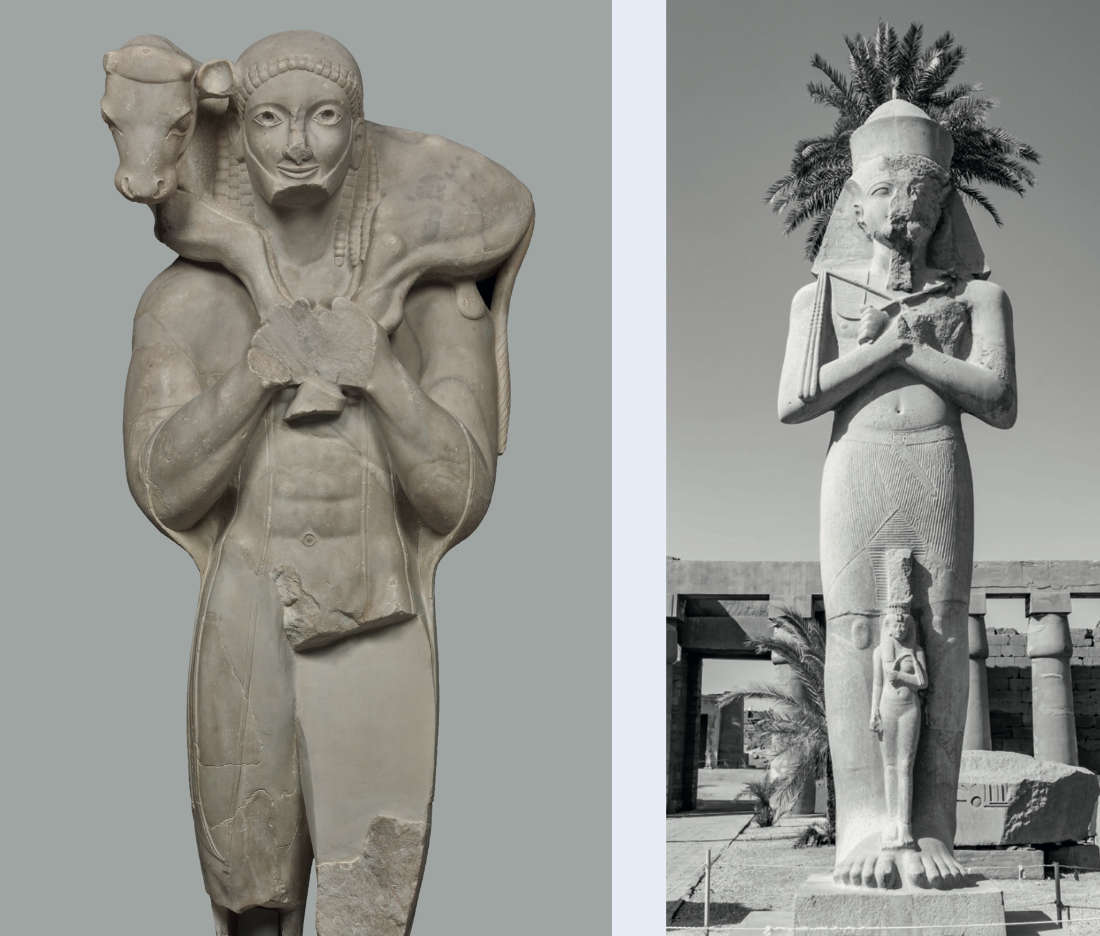

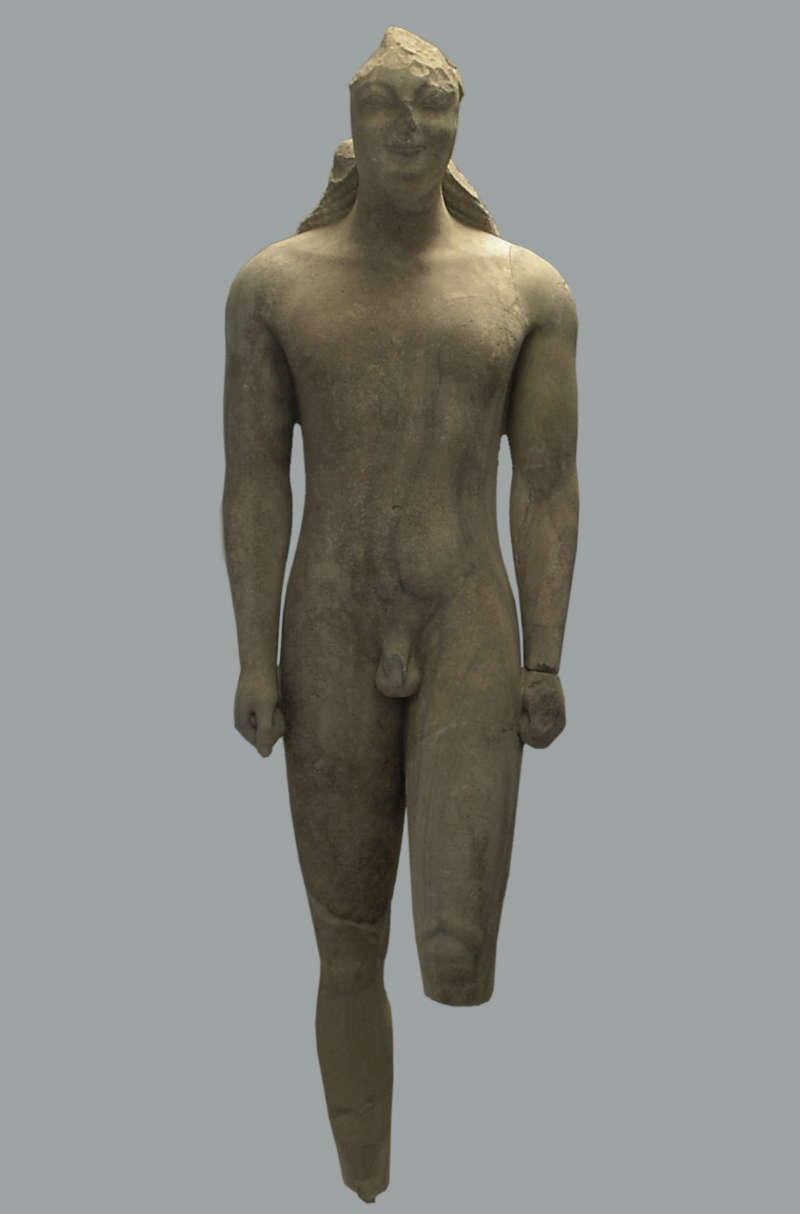

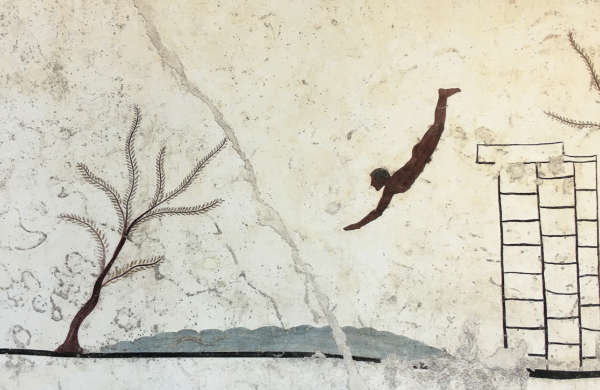

Across this fascinating landscape, moved a person who possessed an uncommon ability to listen to, and understand, what he saw and heard. He travelled in person, it seems, by ship and by foot, as well as in mind, observing, thinking, listening, everywhere he went. This individual was Pythagoras. And the ideas which he brought back from Asia and from Egypt, into the Aegean world of Greece, were to change the course of human thinking for ever. Whatever he had learnt from the East, he transformed; and in that transformation, he nourished the nascent scientific way of thinking of his native Ionia, and enriched its spiritual awareness. He was a precursor - perhaps the most important precursor of all - of a quite distinct current of thought, science and speculation, which we can finally begin to call 'Western'.

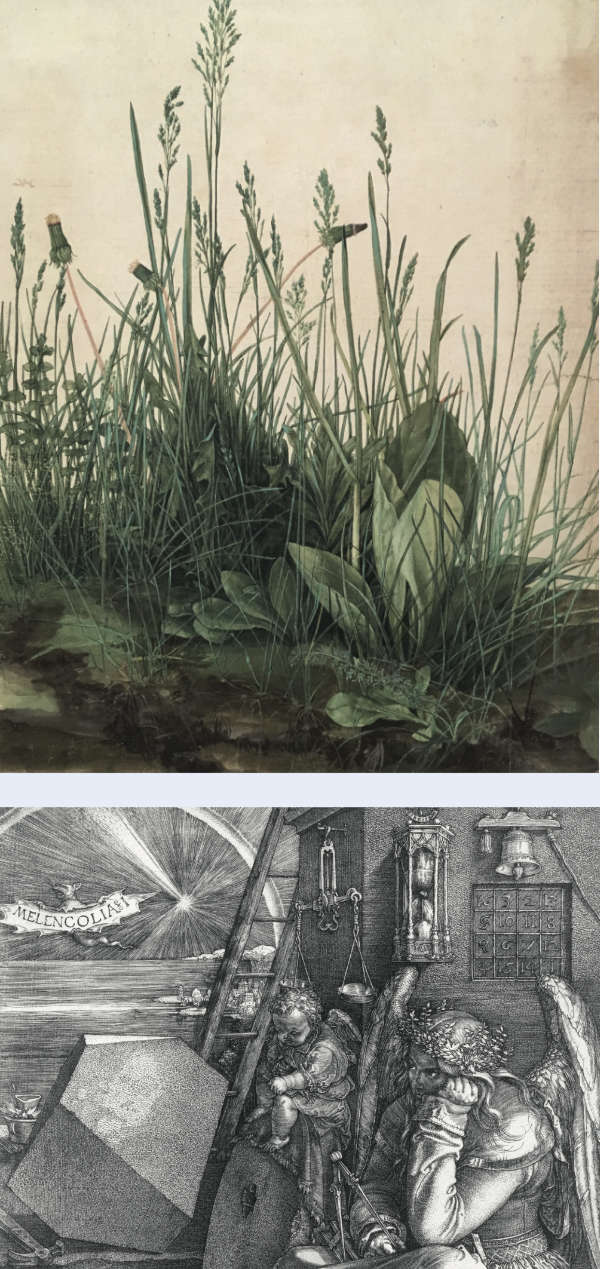

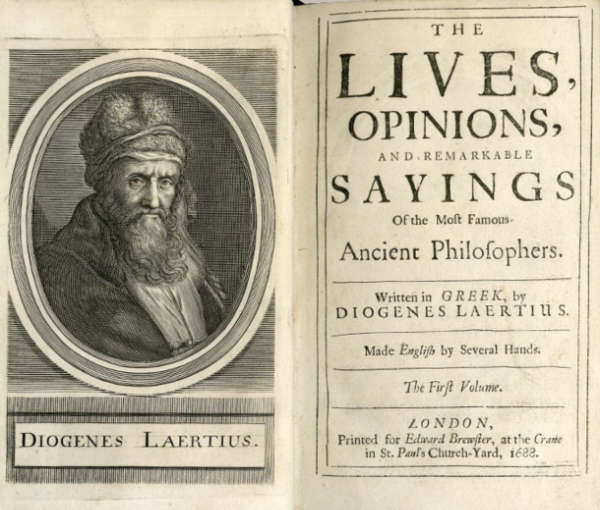

Pythagoras left no writing that has survived. For this reason, his legacy has been buried, garbled, embellished, suffocated, and misunderstood throughout the centuries that followed. Luckily, he preferred to teach not so much with words, but by using mathematics, or acoustic and musical harmony, as well as through his own, very individual, way of being and reacting. By concentrating on these aspects of his legacy, and avoiding the clutter of later accretion, we are able to glimpse, beneath the undergrowth that has obscured him for so long, the crystalline limpidity of his thought. It is a thinking that is clear and liberating, grounded on the perception that order, harmony and beauty are what give meaning to the design of our universe, and to our lives within it.

His is an ancient, but, nonetheless, very relevant story. It can help us today, as we face the problems encircling our natural environment, and as we struggle with the millennia-long legacy of those religious faiths that have corralled our thinking in the intervening centuries since time of Pythagoras. Pythagoras was a free mind - and the boldness and freedom and beauty of his thinking is the subject of this book.